The patient complained of hazy vision — like the light fog on a bathroom window after taking a warm shower. His vision was good and he could still fully function in his daily life, but he knew something was wrong. His vision had changed.

When he arrived in the office of Dr. Christopher Rapuano, Chief of the Cornea Service, after hours of travel, he was frustrated. He just wanted answers. Maybe if his vision were worse, the answer would be clearer. But this fog followed him, day-in and day-out. The doctors he had previously seen were perplexed. What they saw did not fit within any of the usual diagnoses.

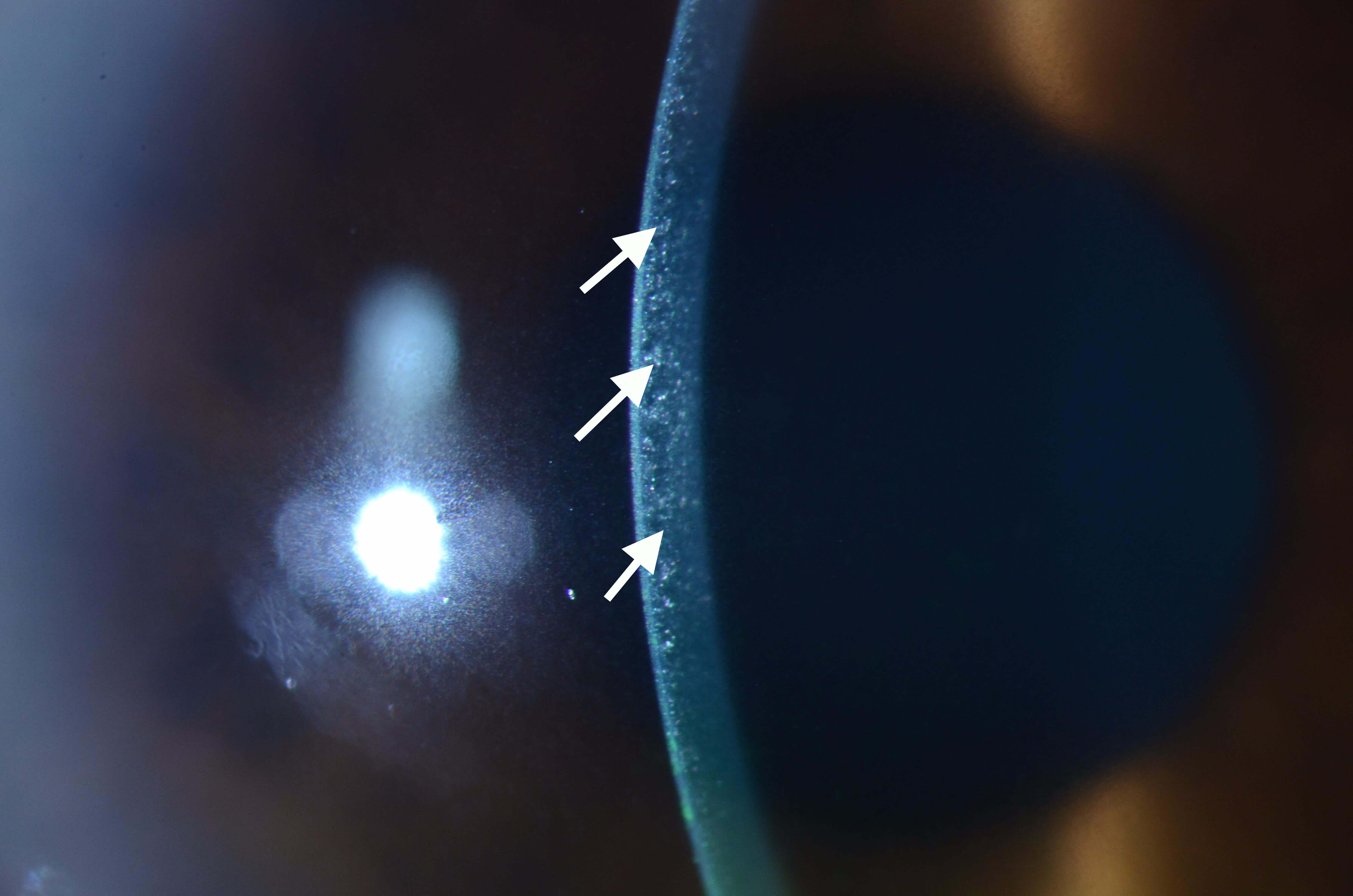

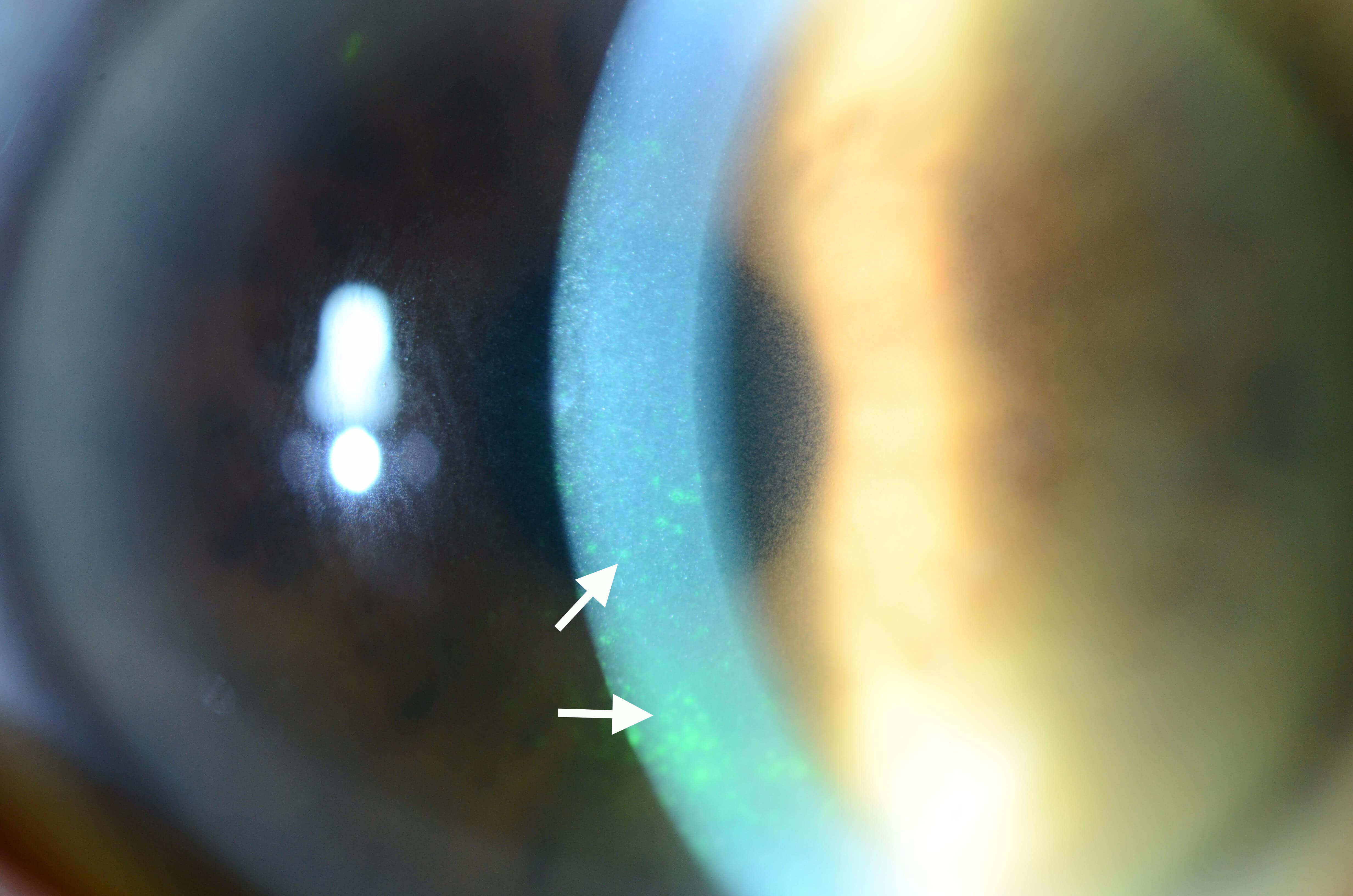

When Dr. Rapuano performed his examination, he saw tiny crystals deposited throughout the man’s cornea. Immediately, a condition called cystinosis came to mind. Although uncommon, cystinosis was the prime suspect to explain the fine cloud of crystalline deposits that were obscuring the man’s vision.

But there was a problem. In cystinosis, larger crystals form. This man’s condition was caused by a sea of thousands of tiny points like nest grains of sand embedded in a glass window. For that reason, Dr. Rapuano set aside his initial hunch and considered another possibility. In a condition called Schnyder crystalline corneal dystrophy (SCCD), fatty substances called lipids sometimes can be deposited in the cornea. But when that happens, the lipid crystals form in dense patterns in the center of the cornea surrounded by a faint halo, like a bullseye. That pattern was not present, so SCCD was ruled out.

Dr. Rapuano now suspected that the crystals were made of protein. If there was too much protein in the man’s blood, the protein could possibly be deposited in the cornea and form this pattern. Remembering a recent paper that described the patterns of deposits in different diseases where proteins are elevated, Dr. Rapuano had some new alternative diagnoses to consider. This pattern was different than polymorphic amyloid degeneration, where the crystals form much larger, defined clumps. Of all the conditions that cause elevated protein levels, Dr. Rapuano wondered if the man might have multiple myeloma, a kind of bone marrow cancer. He referred the patient to a hematologist to find out.

Sure enough, the hematologist found elevated protein levels in the patient’s blood. He believed the problem was a multiple myeloma-like disease and could not believe that the man’s ophthalmologist had made the diagnosis based on what was happening in the cornea. It took time, however, for the hematologist to settle finally on a diagnosis of multiple myeloma because not all of the criteria were met by the man’s condition. But as is the case with many systemic diseases, the eye often provides an early warning sign of problems elsewhere in the body. This patient’s diagnosis was life-changing and difficult, but he was grateful to find it early and begin the regimen of chemotherapy that would be necessary to save his life. Those microscopic crystals, that fog on the bathroom window, and Dr. Rapuano’s experience and sleuthing, gave this man the head start he needed.